Reviews

Review of The House of Dreams – 2007 by Giles Sutherland

Diana Zwibach was born in Novi Sad on the banks of the Danube River and lived there until the age of 12 when, in 1961, she moved with her father and mother to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia. Her father was a radiologist and his talents were much sought after. However, his dream was to take his family to Israel and this dream became a reality when the family moved to Tel Aviv in 1964, allowing her father to take up a post at the Chaim Sheba Hospital and a lecturing position at Tel Aviv University. When in Ethiopia the Zwibach family witnessed an ill-fated coup against the regime of Emperor Haile Selassie and later, in Israel, Diana and her mother were temporarily evacuated to Rome in 1967 to avoid the potential dangers created by Israel’s Six Day War with its Arab neighbours. When Zwibach asked her father why she and her mother were being sent away, her father replied that it was their safety; that he could not bear the thought of loosing those he loved. Tibor Zwibach’s parents, his sister and his niece had perished in Auschwitz along with so many countless others and this trauma had scarred his psyche and remained a deep and irreconcilable burden until his own premature death in 1975 at the age of 56.

Despite Tibor Zwibach’s best efforts to protect his only child, Zwibach’s probing mind and sensitive nature detected a sadness and despair in her father, a man she adored and admired. One of the images in this body of recent work – executed in a very short and intense period of creative energy – shows a male figure: tall, proud, athletic. The predominant tonality of the image is blue and is a homage to Zwibach’s father, her protector. Here, he emerges dream-like from the blue of the Danube after swimming or rowing. This is a central image in this new body of work which focuses specifically on Zwibach’s early childhood in the small, lively, colourful Serbian city. It is a city of dreams, of remembered colours, sounds, smells, people, laughter, movement…a constantly changing panoply of imagery filtered through the lens of memory and the intervening decades of living. It is a childhood remembered, cherished, valued and shared.

These images (there are around eighty in all) differ from much of Zwibach’s previous work – canvases in which she sought to come to terms with her familial history, the history of her people and the traumatic events in which she found herself caught up, as a witness to human brutality and the vast tides of history over which she had no control. Her images were frequently a testimony to pain and, as such, were tableaux of anxiety and confusion – cluttered, coloured, confused – as they reflected an inner turmoil and restlessness. They were the product of the history of post-war Europe and the history of the world beyond.

Here we find Zwibach in a more reflective, contemplative and celebratory mood. The images are almost wholly of a childhood remembered with joy and, as such, they are warm, loving and often convivial. One shows a blond girl with ribbons in her bunched hair holding a doll. In fact, the figure (the artist herself as a young girl) caresses the doll in a gesture of loving protectiveness. This might be seen as metaphor for the mature artist cherishing the memories which provide the basis for this exhibition. In another, a white seagull perches atop a wooden post protruding from the river Danube. However, unlike the dying seagull in Anton Chekhov’s eponymous drama, Zwibach’s bird is a symbol of hope, freedom and beauty. It is a symbol with which the artist herself strongly identifies. Compositionally, this image shares a number of characteristics with others in this series. Firstly, its focus is extremely tight and the main image occupies the majority of the physical space (in this case A3 paper). The ground is a predominant solid red, so that the white bird is thrust forward into the viewer’s gaze and although there is energy and movement in the background and surrounding the central image, the effect is not to distract the viewer’s attention but, rather, to focus it.

Zwibach employs a number of recurrent motifs throughout this new body of work, and while some are both symbolic and realistic, others merely stand for themselves, without allusion, metaphor or symbolism. In another work there is a composition comprising a male and female figure, a donkey and a ladder. Whereas the human figures may allude to family or friends, the donkey is simply a recording of childhood remembrance: donkeys and horses were a common sight in post-war Novi Sad, beasts of burden and transportation. The ladder is a more enigmatic reference and symbolises for Zwibach the possibilities of life: ascend and descend, rather like in the game of snakes and ladders itself.

At heart Zwibach is a figurative painter. Her interest in the human figure can be traced back again to her childhood, peopled with characters, friends, family, guests – a colourful cast who lived in and passed through the convivial household created by her cultured and sociable parents. Added to this was the vibrant life of Nowy Sad where open-air markets, Gypsies and puppet theatre gave her youthful imagination much on which to dwell. In later years her formal training was also highly influential in directing her artistic attention to the human figure; teachers such as Moshe Rosenthalis (b.1922) in Tel Aviv, Joseph Hirsh (1920-1998) and Zvi Tolkovsky (b.1934) of the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and Carol Weight (1908-1997) of the Royal College of Art in London, provoked her interest and offered her an expanded view of the possibilities and purpose of art.

Many of these images, therefore, offer a perspective on the human figure; often figures are grouped in pairs or in greater combinations but sometimes the figure is solitary, isolated within its own world. In one small but powerful image a cross-legged form (it could be either male or female) contemplates a full, rising moon. Zwibach describes her childhood experience and that of her adult life as being solitary, not in a physical sense but emotionally. It’s a theme which has been dwelt upon by numerous artists but it also reflects the human condition; at times we all to a greater or lesser extent, feel a loneliness, an isolation and a disconnection with the life which surrounds us. This is paradoxical in an age which suffers from ‘information overload’ where we are constantly bombarded by noise, images and all the concomitant sensory clutter which our technological age has unleashed.

Even where figures are found in groups of two or more, it’s possible to detect a distance between the ensemble characters; although physically close, these figures rarely touch or entwine. Even in love there is a separateness. In one piece two figures stand on a roof top, watched by a third. The watching figure is partially truncated by the physical edge of the paper on which it is depicted, a deliberate device which emphasises the distance, both in time and space, between the observer and the observed. It’s tempting, irresistibly so, to compare this composition to some of the imagery of Chagall, whose roof-top scenes and dream-like imagery derived from his vision and memory of his native Vitebsk. However, Zwibach describes this work as work of remembrance about her parents. Here, her night-gowned mother dances in the moonlight and her father, less animated, strikes a pose with hands on hips. Gulls fly overhead and the dark blue Dunav can be seen in the distance.

It’s worth mentioning at this point the various techniques Zwibach employs to create her imagery because in a very real sense the medium is the message. Zwibach applies acrylic-based paste to paper and card which she then manipulates using a variety of techniques. Often the paste is rolled and various implements are then employed to mark, scratch and incise the viscous liquid medium. Zwibach describes this process of incision as her attempt to get beneath the surface of things. It’s rather like a river which over a long period of time erodes the rock and soil over which it flows, revealing the underlying geology. In a literal and actual sense, therefore, Zwibach’s work is never superficial; it is, rather, an enquiry, an exploration and an investigation of truth.

The work of committed artists is always in a state of flux, transition and evolution; artists who stick to a prescribed formula of repetition are therefore no longer artists, but repeteurs, a charge which could never be levelled at Zwibach. With maturity comes experience and with this comes a greater understanding of the journey of exploration which art provokes. In these works is possible to sense a shift and a more assured artistic stance; this is mature work and the artist has found her true voice. It is a voice which sings with clarity, precision and great harmony.

Another recurring image in the series of work, and central to any understanding of it, is that of the box, or rather a figure within a box. In the German language koffer refers both to a box and a suitcase and etymologically it is linked to the English word, coffin. Such nuances are important. In one work a female figure is depicted within a box – she may be struggling to emerge, or conversely, she may be being forced into the object. At the risk of falling into the trap which some critics describe at the intentional fallacy, it seems apposite to suggest that for Zwibach the box is a highly charged emotive symbol. In the museum at Auschwitz are displayed, along with room-fulls of other personal effects, the suitcases of the prisoners who were transported there, never to leave. Personal effects are the material testimony to their imprisonment and suffering. The box has contained her, both in the form of a house and also a symbol from which she has constantly endeavoured to escape. Although contained by the constrains of the physical body and its ultimate and inevitable end, the artist, through their art and imagination can escape, at least temporarily, from the literal and metaphorical boxes in which they find themselves.

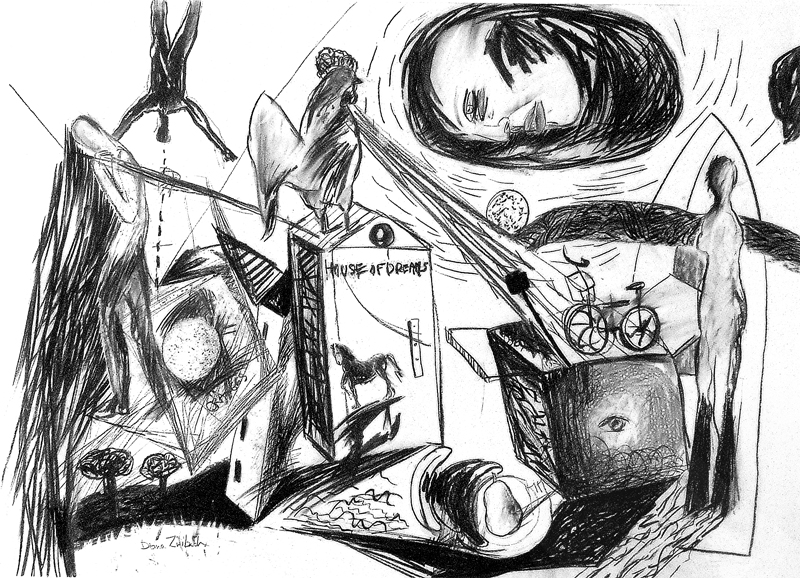

Standing out from the series of small scale works here are three much larger pieces, executed in charcoal. By definition they lack colour, and even tonality, but they are full of movement, energy and passion. These works also autobiographical, a trio which might be termed ‘mindscapes’. Amongst the kaleidoscope of imagery which includes animals, trees, human figures, elements of landscape, a ship and, again, the highly symbolic seagull, it is possible to detect the image of a box or object which is being pulled ‘through’ the rest of the imagery. Here Zwibach is suggesting that memories and some material aspects of life are always present. The past is always being carried by the artist as she moves through life and makes her art. Most of us collect and keep certain objects which are significant to us: mementos, letters, artefacts, images and here Zwibach emphasises that her past is both weighted and precious, something which much always be borne and carried through life.

If Zwibach employs a panoply of symbolism in this series of images then another central and recurring motif is the tree. For Zwibach this conjures the idea of rootedness, or rather the wish for it. Because, as someone who has lived in a number of places around the world and travels constantly, the particular quality of stability has been absent from Zwibach’s life, although her current home, in the north of England, has has given here a wonderful sense of belonging. It is instructive that in this series, which focuses on the idea of home, the tree as leitmotif should occur so frequently. In one image, a female figure dances next to a tree while in another a figure sits in silent contemplation adjacent, again, to a tree. For this exhibition Zwibach has also created a number of small scale books, or what might be termed ‘visual autobiographies,’ and the tree is a central image here also. In one sketch a figure reaches skywards becoming a tree, in an act of metamorphosis. The writer Herman Hesse wrote that “… trees have always been the most penetrating preachers….they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And I revere them when they stand alone. They are like lonely persons…In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfil themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves…”

This seems a particularly apt series of observations when considering Zwibach’s work, for as an artist she too is seeking to represent herself, her life, those she has loved and lost, her home and that strangest and most distant of places, her childhood.

Giles Sutherland

Review of Diana Zwibach’s works 2008 by Robert McDowell

There is so much to say about Diana’s work. Her paintings and drawings are rich in poetic allusions using a wide range of expression that reward contemplation. Her paintings can be lived with for many years and always relied upon each time to reveal new insights, sometimes emotional, sometimes literary, like excerpts from great romantic novels. Describing her work, Diana wrote, “I am concerned with exploring my inner self as it reacts and responds to outside realities. My work celebrates the sensual nature of mankind struggling to achieve moments of peace and harmony in a never ending battle for survival on a spiritual plane.”

Diana trained at great art schools, Bezalel, Chelsea and the Royal College of Art where she was a student contemporary of Linda Sutton whose work shares some similar trait influences. Diana’s work is thoroughly professional, what collectors call ‘investment grade’, yet it is never calculated, contrived, market-driven, but replete with both raw and sublime emotional honesty, today as much as decades ago, much admired by Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Demarco and others. As with the work of British painters of the pop art era and later, such as RB Kitaj and early David Hockney, or Francis Bacon without the horror, Chagall without the folk art, or Kandinsky pre-Bauhaus, also Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach without the impasto or impenetrable darkness, and of course Stanley Spencer if only he had painted more freely and less religiously, sometimes of Rauschenberg meets early Rothko or de Kooning with Picasso at his most primitive. One thinks too of Paula Rego, but painting less studiously, or Tracy Emin, but not so dysfunctional, or like Jacqueline Morreau of whom Terri Windling wrote that her work “is both deeply personal and universal, with a sharp political edge. Her images speak on many different levels, and whisper stories told in multiple voices”.

I suppose what I’m trying to say is that Diana’s work is quite special and unique. It should be represented in Tate Britain and in the collection of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in Brooklyn, New York.

Diana’s paintings combine painterly qualities with figurative drama, subjectivity within an atmosphere that is almost literary, romantic and poetic, with abstract expressionism’s sometimes complex, sometimes simple, broad brush emotional landscapes, with figures that are more people-scape than portraiture or life study, and more theatre than reportage. The source of her integrity is that her painting is journey, exploration of self, and a visual means to discover deep hidden values, finding what it means to hold on to the best of human qualities, to know oneself, to be a survivor. Her subjects, the interwoven stories of her paintings, can be very personal about deep trauma and long-lasting wounds, yet also romantic, healing and victorious, even when set against a backdrop, or in the midst of war, to find also joy, humour and redemption alongside pain and suffering, hope with fear, love with betrayal. She identifies with millions whose personal dramas cannot be disentangled from war, such as in Yugoslavia where she was born, and the Holocaust history of her Jewish forbears, family tragedies, dislocations and the many internecine conflicts of the last century and this. Many dramas, wounds and traumas, small and great, all can be read in these soulful paintings and drawings through which always shines the victory of the human spirit.

In the oil canvasses, the painting is liquid drawing with oil-based or acrylic colours, usually with white-base or pastel hues that denote human presence, interiors or interior thoughts, of reflected light and tight shallow pictorial space, not the intense pure colours of inhuman nature or cosmic space. All her colours carry more symbolism than naturalism, in a carved or etched pictorial space of figurative landscapes, sometimes dreamlike surreal with loose cubist elements, each painting, large or small, finding an iconic look or combination of disparate but complementary images, mood-heavy, but always imbued with a feminine heart that is upbeat and ultimately positive about the human condition, about the capacity of human beings, women especially, to know themselves. Her depictions do not fall into any wells of despond, though they may, in her drawings, sometimes teeter on that brink; more Joycean than Kafkaesque, more French post-impressionist than German Expressionism. Any anguish or brooding thoughts are female and romantic, not male, angry, satirical or resentful. I want to underline this point; her work is thoroughly feminine and feminist in ways I consider more thoroughly so than many or most overtly feminist art that over-uses obvious symbolism such as Judy Chicago or Georgia O’Keefe.

Every quality of paint or line whether a soft exuberance or a sharp stabbing energy are meant to be just so. There are no superfluous or merely decorative elements; absolutely no painting by numbers just to fill in or load up the space. The paintings and drawings can at first look appear in places to have accidental half-finished marks and textures, like unfinished thoughts or incomplete sentences, but every detail is considered and weighted, nothing left in for no reason or without emotion; these are truly professional works in which years of art training and practice, in which one learns to care for every little detail, have not displaced or lost the creative subjectivity of the child, but only enhanced and freed this – what Picasso claimed his whole life’s work was dedicated to achieving. Of all the artists whose work continues to inspire Diana, Picasso is probably the strongest. What is also remarkable in this respect is that Diana’s painting and drawing and printmaking has enjoyed its full-fledged power from the earliest years. I have looked at hundreds of her paintings and drawings and find there is, since art college days, the same constancy of complete integrity of emotional judgment in all her works throughout her career

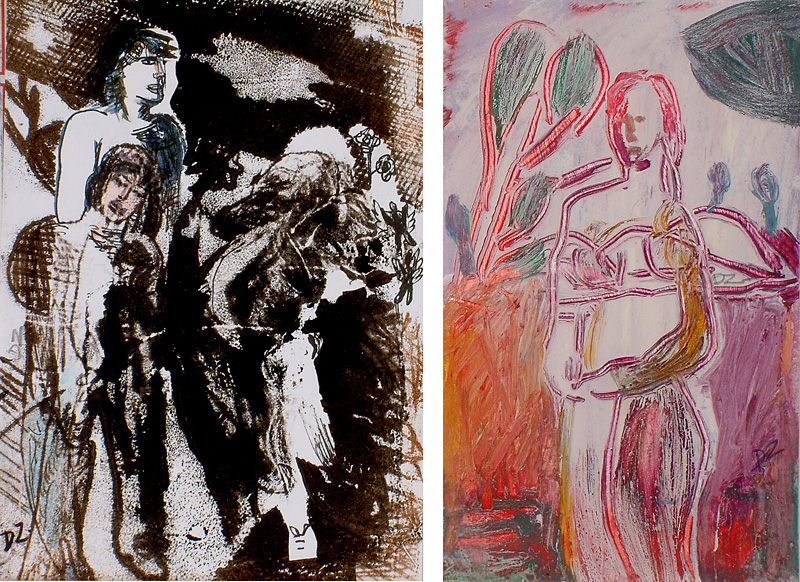

Diana’s drawings (charcoal), often much larger in scale than her paintings, have a strong raking energies that use a much deeper pictorial space and find a kinetic dynamism or automatism forms of abstract expression to deliver searing emotions that possess her female figures or occupy their space. These are portraits and yet not portraits. They are inspired by various versions of herself at different times in her life and of others close to her. Life’s realities she finds most compelling and most real when expressed in human figures; people are entirely central to her life and through which she sees the world. This may be more typically a female than a male view, but surely one we can all agree with.

The figure is most vital in her drawings. These are very dynamic involving all the tacit art knowledge of arm and shoulder movements to deliver energy and imagery from the subconscious, not the careful wrist and conscious fingerwork of delicate painting with fine brushes. Somewhere between careful painting, and repainting, and the one-off explosive drama of giant drawings, there are the sublime planes and textures and delicate symbols of her lithographs and screenprints, which I hope she will return to do more of in the future.

Her paintings and drawings (over seventy in this show) return to the lyricism of her early paintings, though retaining echoes of themes from later works in which she worked to come to terms, as Giles Sutherland recorded, “with her familial history, the history of her people and the traumatic events in which she found herself caught up, as a witness to human brutality and the vast tides of history over which she had no control. Her images were frequently a testimony to pain and, as such, were tableaux of anxiety and confusion – cluttered, coloured, confused – as they reflected an inner turmoil and restlessness. They were the product of the history of post-war Europe and the history of the world beyond.

Diana found a positive resolution to much of this wider drama by discovering colourful life-affirming ways of communicate moral prescriptions in two series, one for Demarco’s “Witnesses to Existence”, 1993-4, and the other, a large series of small works on Lokrum island in the Demarco programme at the 1998 Dubrovnik Festival.

Of Diana’s early works, whose qualities Diana is now returning to, Giles Sutherland said that in them we find, “a more reflective, contemplative and celebratory mood. The images are almost wholly of a childhood remembered with joy and, as such, they are warm, loving and often convivial.”

In many works Diana finds her themes coloured by the interplay between women, of sisterly solidarity, shared emotions, and only sometimes suggesting rivalry or other tensions, often in paintings and drawings of women together alone with shared emotions, and sometimes in a differentiating atmosphere charged by the male presence, not unlike how ballet or contemporary dance uses male and female bodies to express social and romantic themes. Diana is a figurative painter, but not because she cannot work in other ways too, but because it is in figures that she can best feel, sense and explore what is most real in life.

Giles Sutherland wrote that “Her interest in the human figure can be traced back again to her childhood, peopled with characters, friends, family, guests – a colourful cast who lived in and passed through the convivial household created by her cultured and sociable parents. Added to this was the vibrant life of Novi Sad where open-air markets, Gypsies and puppet theatre gave her youthful imagination much on which to dwell. In later years her formal training was also highly influential in directing her artistic attention to the human figure; teachers such as Moshe Rosenthalis (b.1922) in Tel Aviv, Joseph Hirsh (1920-1998) and Zvi Tolkovsky (b.1934) of the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and Carel Weight (1908-1997) of the Royal College of Art in London, provoked her interest and offered her an expanded view of the possibilities and purpose of art.”

Diana Febland (neé Zwibach) was born in the city of Novi Sad on the banks of the Danube, living there until 1961 when her family to Addis Ababa. Her father Tibor was a medical radiologist. His parents, sister, niece, and many of their friends had died in Auschwitz. This trauma had scarred his psyche and remained a deep and irreconcilable burden. The family moved again, to Tel Aviv, in 1964, where her father took up a post at the Chaim Sheba Hospital and lectured at the University. In Ethiopia the Zwibach family witnessed a failed coup against the regime of Emperor Haile Selassie. From Israel, Diana, an only child, and her mother were temporarily evacuated to Rome in 1967 during the Six Day War. In the ‘70s Diana came to England, met Anthony, married and settled in Blackpool. They have three children. War and its incalculable scale touched Diana and her family again, however, in the Serbian-Bosnian-Croatian war of the ‘90s.

The Demarco Gallery and Demarco European Art Foundation in Edinburgh had maintained a dialogue with Yugoslav artists, musicians, dancers and theatre groups for over forty years inviting hundreds to the Edinburgh Festival. This continued during the war and afterwards when Demarco organized a series of exchanges and visits by artists from many European countries. Under these auspices Diana tackled the most painful issues in Witnesses to Existence and at the Dubrovnik Festival and subsequently at other shows in Croatia, Serbia and the UK. Of this she wrote, “This was a very draining and moving experience. The ruins of destroyed and burnt houses are silent monuments to what happened there during the war. The world famous Lipizzaner Horses stables barely stand, where 50 out of 117 were slaughtered. The survivors of Pakrac and Lipik had their own harrowing stories to tell. The last few days of my trip were spent in Dubrovnik which had been besieged and bombed during the onslaught. The three installations are part of the whole work. One of the installations will be shown within the old walled city of Dubrovnik, in a small dark room with a single candle burning. A voice recording reading out words of hope and energy will be played continuously, recorded at St. Thomas’s church, St. Annes’-on-Sea, Lancashire, England. The remaining two installations were exhibited on the Lokrum Island, a short boat trip from Dubrovnik. On a bullet damaged wall within an ancient cloister, 15 paintings and alongside, on another undamaged wall, hang messages sent to me by well wishers from Britain to the Croatian people. The idea for the installation was inspired by this particular wall which brought to mind the wall of tears in Jerusalem.” An echo of this exhibition was held simultaneously in Pakrac and later in August 1998 at the Edinburgh Festival and the Croatian Embassy, London.

Of Diana’s childhood home, Novi Sad, Giles Sutherland wrote that for her it “is a city of dreams, of remembered colours, sounds, smells, people, laughter, movement…a constantly changing panoply of imagery filtered through the lens of memory and the intervening decades of living. It is a childhood remembered, cherished, valued and shared.” Of her paintings about it, he wrote, “Even where figures are found in groups of two or more, it’s possible to detect a distance between the ensemble characters; although physically close, these figures rarely touch or entwine. Even in love there is a separateness. In one piece two figures stand on a roof top, watched by a third. The watching figure is partially truncated by the physical edge of the paper on which it is depicted, a deliberate device which emphasises the distance, both in time and space, between the observer and the observed. It’s tempting, irresistibly so, to compare this composition to some of the imagery of Chagall, whose roof-top scenes and dream-like imagery derived from his vision and memory of his native Vitebsk.

However, Zwibach describes this work as work of remembrance about her parents. Here, her night-gowned mother dances in the moonlight and her father, less animated, strikes a pose with hands on hips. Gulls fly overhead and the dark blue Dunav can be seen in the distance.”

He continued, “It’s worth mentioning at this point the various techniques Zwibach employs to create her imagery because in a very real sense the medium is the message. Zwibach applies acrylic-based paste to paper and card which she then manipulates using a variety of techniques. Often the paste is rolled and various implements are then employed to mark, scratch and incise the viscous liquid medium. Zwibach describes this process of incision as her attempt to get beneath the surface of things. It’s rather like a river which over a long period of time erodes the rock and soil over which it flows, revealing the underlying geology. In a literal and actual sense, therefore, Zwibach’s work is never superficial; it is, rather, an enquiry, an exploration and an investigation of truth.

“…Another recurring image in the series of work, and central to any understanding of it, is that of the box, or rather a figure within a box. In the German language koffer refers both to a box and a suitcase and etymologically it is linked to the English word, coffin. Such nuances are important. In one work a female figure is depicted within a box – she may be struggling to emerge, or conversely, she may be being forced into the object. At the risk of falling into the trap which some critics describe at the intentional fallacy, it seems apposite to suggest that for Zwibach the box is a highly charged emotive symbol. In the museum at Auschwitz are displayed, along with room-fulls of other personal effects, the suitcases of the prisoners who were transported there, never to leave. Personal effects are the material testimony to their imprisonment and suffering. The box has contained her, both in the form of a house and also a symbol from which she has constantly endeavored to escape. Although contained by the constrains of the physical body and its ultimate and inevitable end, the artist, through their art and imagination can escape, at least temporarily, from the literal and metaphorical boxes in which they find themselves.

“Standing out from the series of small scale works here are three much larger pieces, executed in charcoal. By definition they lack colour, and even tonality, but they are full of movement, energy and passion. These works also autobiographical, a trio which might be termed ‘mindscapes’. Amongst the kaleidoscope of imagery which includes animals, trees, human figures, elements of landscape, a ship and, again, the highly symbolic seagull, it is possible to detect the image of a box or object which is being pulled ‘through’ the rest of the imagery. Here Zwibach is suggesting that memories and some material aspects of life are always present. The past is always being carried by the artist as she moves through life and makes her art. Most of us collect and keep certain objects which are significant to us: mementos, letters, artefacts, images and here Zwibach emphasises that her past is both weighted and precious, something which much always be borne and carried through life.

“If Zwibach employs a panoply of symbolism in this series of images then another central and recurring motif is the tree. For Zwibach this conjures the idea of rootedness, or rather the wish for it. Because, as someone who has lived in a number of places around the world and travels constantly, the particular quality of stability has been absent from Zwibach’s life, although her current home, in the north of England, has given here a wonderful sense of belonging. It is instructive that in this series, which focuses on the idea of home, the tree as leitmotif should occur so frequently. In one image, a female figure dances next to a tree while in another a figure sits in silent contemplation adjacent, again, to a tree. For this exhibition Zwibach has also created a number of small scale books, or what might be termed ‘visual autobiographies,’ and the tree is a central image here also. In one sketch a figure reaches skywards becoming a tree, in an act of metamorphosis. The writer Herman Hesse wrote that “… trees have always been the most penetrating preachers….they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And I revere them when they stand alone. They are like lonely persons…In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfill themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves… This seems a particularly apt series of observations when considering Zwibach’s work, for as an artist she too is seeking to represent herself, her life, those she has loved and lost, her home and that strangest and most distant of places, her childhood.”

To this I only wish to add, as someone who has several of Diana’s paintings in my collection, alongside works by Beuys, Hamilton Finlay, Paolozzi, Tinguley, Donagh, de Saint Phalle , Corneille, Merz, Rotello, Hoch, and many more great artists in the Demarco Archive collection (of which I am deputy Chairman), also in Edinburgh, that her work stands up as strongly as any of these more famous names and her work should be avidly collected and cherished by any who take art collecting seriously.

Robert McDowell